The village of Bomokoi in the Chikiti tehsil, near the Andhra border lends its name to the bomokoi sari. It is not a coastal village; yet the sea is very close. The Vaishanava Chikiti ruler patronised, along with theatrical dance and stilt opera, the Bomokoi sari. The bomokoi represents one of the few non-ikat weaving traditions of Odisha.

Created with the three shuttle weaving technique and the extra heald shaft design on primitive pit looms, made it a labour intensive product, and hence expensive. The bomokoi sari was traditionally worn dominantly by high-caste brahmins during rituals and ceremonies. Certain saris have specific religious purposes: ‘The white badasaara sari is used by the Soura and Kandha tribes to wrap the statues of their deities whereas the kala badasaara is draped behind the image of the goddess Thakurani’.

-

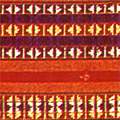

Field: The bomokoi are created in coarse low-count count cotton but are always brightly dyed (often black, red, or white grounds). The body of the sari is ‘accented with a single buttah or motif of a bird on a tree.’

-

Borders: Supplementary weft and warp borders. For the border, popular motifs are ‘dalimba or pomegranate corns and saara or seeds topped with a row of kumbha or temple spires’. Both the ‘dalimba and the saara are diamond shaped beads where the former has a dot within and the saara is halved vertically.’

-

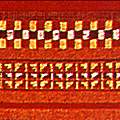

Endpiece: Supplementary weft and warp end-pieces. A broad band of supplementary warp patterning, creating a latticework of small diamond shapes is the usual design.

The fields warp threads were ‘cut and re-tied to different coloured warps for the endpiece’, thus creating an unusually dense layer of colour for the (fairly large) endpiece. This was known as muha-johra or ‘end-piece with joined threads’ (muha = face; johra = join). ‘To achieve a solid colour effect in the pallav, two different coloured warp threads are twisted with starch and joined at the junction where the pallav and body meet.’ (A muha-johra bada-saara is a sari that is ‘blood red in colour and has dotted diamonds [saara] in the border’.)

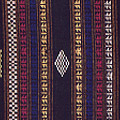

In the bomokoi sari, on a ‘bright background, the weavers create panels of contrasting motifs in the anchal or pallav‘. The motifs are many: karela or bitter gourd, the atasi flower, the kanthi phul or small flower, macchi or fly, rui macchi or carp-fish, koincha or tortoise, padma or lotus, mayura or peacock, and charai or bird being some of the more common ones. Motifs are freely composed; unlike other traditional saris, ‘the pallav pattern does not have any regular grading of motifs, like for example, heavy to light’. As only rich Brahmins wore this sari, each piece was different, thus making each creation an exclusive one.