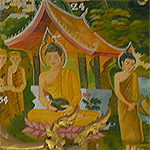

The religious art of Laos is primarily Buddhist and central to it is the Buddha image, depiction of events from the Jataka tales – folk tales written down after the Buddha’s death describing the animal and human forms he had taken in his past 550 lifetimes on his journey to enlightenment, mythological stories and religious symbols. These images, paintings and carvings were created, not to please, but as objects of respect and devotion and their purpose was to instruct, enlighten and deepen faith, bringing merit to both the creator and the person commissioning the object.

Somkiart Lopetcharat in his book, “Lao Buddha – The image and its history”, traces the history of Buddhism and the art of the Lao Buddha in the region and the influences that shaped it, at each stage of its development. Like most Asian countries, Buddhist art in Laos, represented collective knowledge and wisdom that developed and evolved over time. Art forms were copied, duplicated, followed and eventually refined and assimilated into the Lao art traditions, creating a truly Lao style.

BUDDHISM IN LAOS IN BRIEF

To understand the development of Buddhist art, one needs to trace the advent and spread of Buddhism in the country, as well as follow the broad social and political alliances and influences of that time. All these factors contributed to religious art, its origin and its development.

The first Lao Kingdom, Lan Xang was founded in the 14th century by King Fah Ngum after he conquered and unified the lands north of and including Luang Prabang, Xieng Khouang and the Khotrat plateau. Luang Prabang, named after Pra Bang, the Buddha image, remained the capital of Lan Xang for approximately 200 years, until it was moved to Vientiane in the mid 16th century.

In the year 1358, King Fah Ngum’s wife Queen Kaew Kengya, of Cambodian origin and a devout Buddhist, asked him to establish Buddhism in Lan Xang. The people of Lan Xang at that time followed various animist practices. Fah Ngum sent tribute to the Khmer king, in Cambodia, and requested for a Buddhist mission to Lan Xang. The Khmer King sent a mission of monks, headed by Phra Mahapasaman. The Khmer king also sent The Pra Bang, and sculptors, goldsmiths, silver-smiths, blacksmiths, and musicians to accompany the monks.

(The Pra Bang, regarded as the protector of the Lao kingdom, is an image of the Buddha, created in the Mon-Khmer style and cast in a mixture of brass, gold, silver, zinc and copper. It is believed to possess strong protective powers. The image is 83 centimeters tall, weighs 52 kilograms, and portrays the Buddha standing with arms raised forward at the elbows, palms facing forward. This hand gesture signifies Bestowing Favours, assurance and protection. Tradition maintains that the relics of the Buddha are contained in the image.

Phra Mahapasaman led the procession with the Pra Bang along the Mekong River to Vientiane. A three-day celebration of prayer was held to mark their arrival. The Buddha image was then transported to Vieng Kham, amidst similar celebrations. The sacred Buddha image was then to be transported to Chieng Thong (Luang Prabang), but could not be carried. This was interpreted to mean that The Pra Bang wished to remain in Vieng Kham.

During his time, King Fah Ngum and his queen promoted Buddhism. They built a temple for the monks, in the north, which later came to be known as the Wat Pasaman and numerous other temples. A reliquary was added to this in 1364 to house the relics of the Buddha’s right thumb. Later Wat Phra Kaew was built for The Emerald Buddha, which the queen had brought with her from Cambodia.

But, the Golden Age of Buddhism came some two centuries later. The 16th century witnessed an extraordinary flowering of Buddhist art and architecture in Lan Xang, with three illustrious kings – Wisunarath (1501-1520), Photisarath (1520-1550) and Sai Setthathirat I (1550-1571). By the 17th century, the kingdom of Lan Xang entered a period of decline marked by dynastic struggle and conflicts with its neighbors.

It was during the reign of King Suriyawongsa Thammikaraj (1638-95), once again, a number of temples were built, and Buddha images were cast. His rule brought peace to the land and Vientiane emerged as an important centre for Buddhist learning. According to Lao belief, the king sat upon the throne because of his good karma and he was expected to continue that good work during his lifetime by following the principles of kingship, supporting the Buddhist order and promoting Buddhism through royal patronage and other means.

After his reign, however, the kingdom broke up into three separate states: Luang Prabang in the north, Vientiane in the center, and Champassak in the south. Eventually all three came under Thai rule. This period is characterised by a decline in Lao Buddhist art. While temples continued to be maintained, new ones were not built nor were fresh Buddha images cast.

Following their colonization of Vietnam, the French integrated all of Laos into the French empire. The Franco-Siamese treaty of 1907 defined the present Lao boundary with Thailand.

THE LAO BUDDHA

Somkiart Lopetcharat in Lao Buddha – The image and its history writes, “The original Buddha images which came from Cambodia continued to exert an influence over Lao Buddhist art until the Lan Xang sculptors were able to create their own original and identifiable style. At this point, the art of the Lan Xang Buddha image became distinctly Lao. The art of the Lao Buddha image is conservative and traditional, adopting only influences that blended rather than clashed with it. Thus, the present-day Lao Buddha images differ little from those created in the past.”

The early Buddha images were heavily influenced by the Pra Bang. A distinctive Lao style began to emerge only between 1456 and 1520. It blended the Khmer post-Bayon, Lanna, and Sukhothai styles with elements from the early Ayutthaya period.

During this period, the casting of Lao Buddha images was done in components. For example, the radiance was cast separately from the head and later joined to it; the pedestal was cast separately and sometimes served as a reliquary. The various components were assembled by means of tonged and grooved joint techniques indicating skilled craftsmanship.

The alloy was copper and tin mixed with lead, silver, and gold. The Buddha images of this period are very beautiful.

During the Golden Age of Buddhism, 1520-1770, the images show an originality of style. Somkiart Lopetcharat writes, “The eyes, which were formerly downcast, now look straight ahead and are wide open. They are lined with silver or mother-of-pearl. Inlaid black sapphires serve as the pupils. The lips are covered with silver or in a gold and copper alloy. A wide variety of styles, quite high and beautiful, might be derived from the Ayutthaya-Prasatthong style. The selection of metals and the casting indicate exquisite craftsman-ship. Images cast by royal command have a greater percentage of gold. An alloy with a percentage of silver and gold was one of the identifying features and very popular solutions of alloy mixtures were used in the casting of Lao Buddha images during this period.”

It is important to understand that while the depiction of the Buddha image itself evolved and changed – both in terms of appearance and expression and the techniques and materials used; what did not change are the postures and hand gestures and their interpretation.

TRADITIONAL RULES FOR MAKING BUDDHA IMAGES

A Buddha is said to have 32 features that represent his exalted state and distinguish him from ordinary human beings; 31 characteristics can be depicted in a statue or an image, only one characteristic “clear and far reaching voice” has to be imparted to a believer. However, these traditions vary from country to country and there are no universal norms regarding the Buddha’s appearance. Most Buddha images have some of the following characteristics:

- Hair curled in tight snail-like whorls representing his short hair which he cut as a sign of renunciation and humility

- Elongated ears (from wearing jewelry as a young prince)

- All the fingers and toes are of the same extended length

- Beak like long aquiline nose

- Broad shoulders

- The bulge or protrusion at the top of his head signifying great mental powers and the Buddha’s transcendent knowledge

- A whorl of hair between the eyebrows that is also often depicted as a dot, a sign of his transcendent nature

- Simple garments of a monk: a robe, and sometimes a shawl, no adornments

- A serene expression and half-closed eyes signify meditation and inner peace

- Eyes half-open to show awareness and compassion for the devotee

- Often his lips reveal the hint of a smile, another sign of compassion

Some common symbols on Buddhist paintings and carvings, indicating the Buddha’s presence are:

The Lotus: A sign of spiritual perfection – the flower rises and blooms unsullied from the muddy waters so the devotee attempts to rise above the impure world and become transformed through enlightenment into a spiritually perfected being.

The Wheel (chakra): represents the doctrine preached by the Buddha in his first sermon, “turning of the wheel of dharma”, after attaining enlightenment. The wheel’s motion is a metaphor for the rapid spiritual change engendered by the teachings of the Buddha

MEANING OF BUDDHA IMAGES

Every Buddha figure communicates meaning. One of the most important characteristics of a Buddha image are the mudras or hand gestures – each symbolizes some aspect of the Buddha’s life or denotes a special characteristic. These well-defined gestures have a fixed meaning throughout all styles and periods of the Buddha image. There are several symbolic hand mudras and nearly all Southeast Asian Buddha images are made in one of them:

Dispelling Fear or imparting fearlessness: This represents the Buddha promising his followers tranquility, protection and courage if they accept and follow the Law.

Generally the right hand is raised to shoulder height with the palm facing outwards and fingers pointing upwards in a universal gesture of protection, benevolence, and peace and the dispelling of fear. The wrist is bent at a right angle to the forearm. The gesture is sometimes made with both hands. In Laos, this mudra is associated with a walking Buddha.

Teaching: Here, the right hand is raised with palm facing outwards and the index finger and thumb forming a circle. The other three fingers point upward. The circle formed by the thumb and index finger is the sign of the Wheel of Law or perfection. This gesture is often portrayed with both hands.

Teaching the First Sermon: Both hands are together at the chest with fingers on one hand forming a circle representing the “wheel of law” while the other hand touches the wheel to set it in motion or “to turn the wheel of Dharma”. The hands are generally held close to the chest, at level with the heart. It symbolises one of the most important moments in the life of the Buddha, the occasion when he preached to his former companions the first sermon after His Enlightenment, in the Deer Park at Sarnath, representing the beginning of Buddhist teaching.

Meditation: Both hands resting together on the lap with palms facing upwards. The right hand is on top of the left hand. The Buddha is most often seated in the half-lotus posture or full-lotus posture with tightly crossed legs, so that the soles of both feet are visible. The gesture symbolizes perfect balance of thought and tranquility. In South East Asia, this mudra is frequently used in the image of the seated Buddha.

Calling the Earth to Witness: shows the Buddha seated with crossed legs, palms facing inwards, the fingertips of the right hand touching the ground as he “calls the earth to witness” his enlightenment. The gesture symbolizes unshakable faith and resolution and is the most common posture for Southeast Asian temple images.

Passage to Nirvana: The reclining Buddha represents the Buddha’s passing away and symbolizes complete peace and detachment from the world.

Offering or Wish Granting: depicts the standing Buddha with arms outstretched in front of his body, palms opened out and the tips of the fingers pointing downwards to the earth. This mudra represents the Buddha blessing his followers and offering of the Buddhist teaching to the world. Sometimes the teaching, and its benefit, is symbolically represented by a small piece of medicinal myroloban fruit.

This mudra symbolises offering, giving, welcome, charity, compassion and sincere boon granting. It is nearly always made with the left hand.

Two types of standing Buddha images are distinctive to Laos. These are:

Calling for Rain: Depicts a majestic Buddha standing with hands held rigidly at his side, fingers pointing towards the ground. At the bottom, the figure’s robes flare out upwards on both sides in a perfectly symmetrical fashion that is also unique and innovative.

Contemplating the Bodhi Tree: In this image the Buddha is standing in much the same way as in the ‘Calling for Rain’ pose, except that his hands are crossed at the wrists in front of his body. (The Bodhi tree, or ‘Tree of Enlightenment’, refers to the large banyan tree that the historical Buddha purportedly was sitting beneath when he attained enlightenment in Bodhgaya, India, in the 6th century BC.)

Midget Lao Buddha Images: Since ancient time, people of many religions have cast midget or miniature idols including Buddhas. In ancient times these tiny Buddhas were always wrapped up in a piece of doth and tied about the head above the ears while people were at work or in battle. The very tiny Lan Xang (Lao) Buddha images in alloys of various metals are classified as amulets.

FEATURES OF THE LAO BUDDHA

Standing Buddha images exhibit Khmer and Thai influences, while seated images are uniquely Lao, and show characteristics such as a beak-like nose, extended earlobes, tightly curled hair, and long hands and fingers.

The Radiance

The shape of the radiance depended on the origins of the creator of the image and took many shapes:

- cover of an earthenware pot

- a glass ball

- lotus bud

- high pointed-cone shape on a square base decorated with lotus buds beneath

- flame shape, during ‘The Golden Age’

- clusters of lotus petals. Luang Prabang Buddhas feature lotus clusters engraved delicately.

Ear Shape

The shape of the ears of the Lao Buddha images is made in various designs. In the early stages, the ears were flat and plain with a curved conch shell acting as the ear cavity. Later, the shape became meticulous, and the line from beginning to end inside the ear attests to outstanding craftsmanship.

The Pedestal

The pedestal is a prominent feature of the Lao Buddha images. The respect and ardent faith the Lao had in Buddhism has caused images of the Buddha to be installed upon high pedestals.

MATERIALS

Lao Buddha sculptures use a variety of mediums, including bronze, wood, gold and silver and precious stones.

Of these, bronze is by far the most common and has been used to create many important Buddha statues, including:

- the images at Wat Manorom in Luang Prabang (14th century) – only the head and torso remain and reveal that the colossal bronzes were cast in parts and assembled in place

- The images at Wat Ong Tu and Wat Chanthaburi (Wat Chan) in Vientiane (16th century).

Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin. Other materials are often added and this determines the appearance of the image. In Laos, like in Cambodia and Thailand, the bronze, which is called samrit, includes precious metals, and often has a relatively higher percentage of tin. This gives the cast image a lustrous dark gray color. A higher copper and, probably, gold content gives a muted gold color, such as in the image of the Buddha of Vat Chantabouri in Vientiane.

Brick-and-mortar are also used for large images.

Wood and ceramics are popular for the tiny, votive images found in cloisters or caves. Wood is also very common for large, life-size standing images of the Buddha.

Smaller images are often cast in gold, silver or precious stone.

Wood

There is an abundance of wood in Laos and many of the Buddha images, both large and small, and wooden carvings, decorative friezes have been made from the best available rich tropical hardwoods such as:

- Teak – a durable, hard wood with a rich brown color.

- Yemane – a moderately hard wood with a whitish colour that sometimes has strains of green or gray.

- Padauk – a beautiful reddish colour

- Ebony – a dark coffee brown colour

- Sandalwood – a caramel colour wood with a rich aroma

- Rainwood – because of the uneven colour this wood is used not for carving but for being painted on

BUDDHIST PAINTING and CARVING

Many scenes are carved or painted as murals on temple walls, such as the Buddhist sculptures in the Pak Ou caves. Buddhist painting features Buddha images, representations from the Jataka tales and the Lao version of the Ramayana known as the “pharak pharam” and also other symbols and representations. There are strict rules that govern the depiction of the Buddha and other important figures. The size, position or placement of a figure, with respect to the central figure or deity, indicates its importance or hierarchy in a story or representation.

These paintings are made using simple lines and plain colour, with no shadow or shading. Their purpose was to serve as a means of enhancing religious worship. They took two main forms:

- bas-relief murals

- painted preaching hanging cloths

Bas-relief murals

Lao temple murals were carved or etched directly onto dry stucco, making them extremely vulnerable. Some of these murals exist even today – but have been restored many times, often using modern pigments and materials. Despite this, the quality of work is often superb; some excellent examples may be seen at Wat Sisakhet in Vientiane, at Wat Pa Heuk and Wat Siphouthabath in Luang Prabang.

Painted preaching hanging cloths

Painted hanging cloths were generally made by painting scenes from the jataka or pharak pharam onto rough cotton sheets. These were displayed while monks were preaching.