Woollen pile carpets have played a prominent part in the textile history of Pakistan. At present in Pakistan a wide variety of carpets and floor coverings are being produced.

In the districts of Kalat, Quetta and Pishin, sheep’s wool is used for the making of felt. The namda or thappur rugs /durries, carpets /galeecho, saddle bags /khurzeen and horse and camel blankets caps are some of the well known products created by felting. Besides these felting is also practiced for domestic use for bags, hats, winter coats, capes and waistcoats.To make the felt the wool is beaten with sticks and carded until it is clean. It is then evenly spread on woven mats or dampened sheets of cloth and sprinkled with a soapy water mix. Layer upon layer of wool is built up in this manner until the desired thickness is obtained. Brightly dyed tufts of wool are then inserted symmetrically into the top layer to form patterns. The wool and mat are rolled up tightly, rotated backwards and forwards by using pressure, and the roll is then securely tied. This manipulation allows the dampened fibres of wool to bind together or interlace in a solid layer which is then opened out to dry and harden.

Far more intricate than the motifs on namda are the chain-stitched patterns on blankets and burlap called gabbas. Here woollen yarn in different colours is used on white or dyed felt to trace geometric or animal motifs or stylised patterns representing chinar leaves, grapes, irises, almond and cherry blossoms. In most cases the ground is completely covered with geometrics or floral patterns, scenes of natural beauty or pictorial stories – such as hunting scenes, wedding parties and celebrations. In recent years younger craftsmen have produced gabbas with chain-stitched embroidery in wool on jute that possess all the qualities of old masterpieces.

The more important centres of namda production with such motifs are in Swat, Hyderabad, and the north-western part of Balochistan.

Emperor Akbar (1556-1605), is credited with having started the production of all cotton carpets in the South Asian subcontinent. The decisive factor must have been the need for rugs and tapestries to suit a hot climate and based on the more abundantly available raw material. The validity of these considerations is reflected in the large-scale production of durries that continues till this date. In the past these flat-woven cotton rugs were frequently made in villages by the women of each household for use as bedding and floor-coverings. Woven in different sizes the durries were used for multiple uses – cot mat covers, floor coverings for big assemblies, prayer rugs, and wall-hangings.Now woven on horizontal looms with machine-made, coarse cotton yarn by organised teams of weavers the practice of using hand-spun yarn continues in the village.

Large centres such as Lahore, Multan and Bahawalpur were known for their large, boldly patterned durries, often in blue-and-white geometric design, which were commissioned for local mosques and interiors. Many of the finest durries were made not by professional craftsmen but by prisoners in jails: in the Punjab, the jails at Multan and Sahiwal (formerly Montgomery) were especially noted for their durries, but prisons in Sindh and many other parts of the subcontinent were also producing fine examples. There is also a tradition of creating patterns on plain durries through the process of block printing.

It is generally accepted that the art of the hand-knotted carpet, as practised for more than a thousand years, was developed in Iran. This belief rests on the fact that the oldest surviving carpets were produced by Iranian craftsmen in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries when during the reign of Shah Abbas Safavi (1586-1628) they reached the peak of their glory. The same period witnessed the rise of the Mughal carpet which forms a valuable part of the conglomerate of many national schools loosely held together under the label of Persian carpets. Emperor Akbar mobilised craftsmen in various media and one of his most ambitious projects was the founding of imperial carpet workshops at Lahore, Agra and Murshidabad.Much has been written in recent years about the features of the Mughal School that distinguished it form the styles evolved in Iran. While the Lahore carpet-weavers adopted both the standard knots (Turkish and Persian) and some of the stylised motifs executed throughout the carpet countries, they evolved their own patterns for the prized varieties – the hunting, garden or floral carpets. Not only were their trees and flowers, animals and hunters, drawn from life around them, they are credited with having achieved greater naturalism and mobility than their counterparts in Kashan or Ishpahan. Also they were among the most successful artists who could increase the pleasing impact of a floral pattern by providing adequate relief or using a light ground. As for the ultimate test of the quality of a carpet, the fineness of the wool and the knot, chroniclers have recorded that the Lahore carpets had up to 1,200 to 2,500 knots to a square inch and that the wool of the carpets made of the royalty, like those woven for Emperor Shahjehan, was indistinguishable from silk. A measure of the unbelievably high standard of craftsmanship attained by the Lahore carpet-weavers of the Mughal School is provided by a small piece made in 1907, long after the decline of the imperial workshops.

The whole process involved in the preparation of hand-knotted carpets furnishes a fascinating study of human ingenuity. To begin with the basic raw material – wool – must be carefully selected. Fortunately, the sheep traditionally bred in Balochistan, Northern Areas and Cholistan yield fine quality wool. A crucial pre-weaving operation is the dying of wool in the desired colours. To say only that for centuries the craftsmen depended upon vegetable dyes and are now using synthetic varieties is to ignore the special skills developed by the dyers and on which the appearance of the carpet and the fastness of its colours depends.

The most essential part of the carpet-weaver’s equipment is a wooden (or iron) loom which may be fixed to the ground horizontally, in the fashion adopted by the nomad weavers, or vertically, as is the case in most indoor units. Yarn for the warp is stretched form beam to beam. The length of the beam determines the width of the carpet though there can be no limit to the length of the beam itself, except for that imposed by the size of the working space available to the craftsman. The tools used by the weavers are: a knife to cut the yarn after the knotting; a comb to set the wefts; and shears to trim the pile.

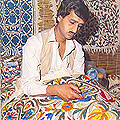

The beams of the common loom are supported by two vertical posts firmly driven into concrete or heavy logs of wood. After the warp has been stretched arrangement is made for the crossing of its threads. Before the knotting of the wool pile begins about an inch of the warp is woven like ordinary cloth by passing the woof threads through the warp. For knotting the weaver sits on a bench in front of the loom. When several weavers work on a single carpet each one of them is responsible for a part of the breadth of the loom. Above the weaver’s head hang balls of wool in the required colours. He ties knots on the warp-spread according to the given pattern by pulling down the yarn of the proper colour and passing it round the threads of the warp to form a knot. The ends sticking out in front are cut off with the knife which descends on the thread simultaneously with the completion of the knot. When a row of knots has been completed a thread of woof is passed from the other end and the pattern is beaten into place with the comb. The process is continued till the carpet is completed and taken off the loom by cutting the warp threads. The loose threads are knotted to form a fringe and the long sides of the carpet are bound with wool threads to make firm edges. Throughout the process the weaver depends more than anything else on his fingers and eyes, both trained to deal with the exacting demands of the craft and to make judgements with astonishing speed and precision as if electronically co-ordinated. The slightest error at any stage can cause irreparable damage.

The washing and cleaning of the finished carpet is no less a test of skill than weaving. Carefully, through several processes and use of chemicals, dust particles are removed from the weave and colours made fast and well-defined.

Apart from the quality of wool what determines the value of the carpet is the fineness of knotting. Both the standard knots the Ghiordes (Turkish) style of knotting around two warp threads, and the Sehna (Persian) style of knotting around two warp thread and looping under the next – are executed in Pakistan but the latter is more common. An average quality carpet has around 250 knots per square inch but in finer pieces the number may range between 500 and 1,000. A skilled craftsman can tie 10,000 to 14,000 knots a day. To facilitate speedy knotting the design is read out to the weaver by a Talim reader. The Talim is a graph of knots in various colours prepared by specialised on the basis of the pattern and colour scheme laid down by the designer craftsmen in other fields to illustrate a book, illumine a glass panel or decorate architecture.

In the recent years, carpet business has become a vast enterprise with a turnover of millions of dollars and the entire production is controlled by merchants. The bigger traders have installed looms at their workshops and hire labour to work there. Although the number of weavers so employed is around ten per cent of the total in the country, the vast majority of weaver working on looms installed at their homes in villages also depend on the traders, usually a weaver enters into a contract with a merchant who provides the carpet design and raw material. In many cases women and children provide skilled and unskilled support to the head of the family. Since more than one person may work on a carpet and the amount of labour required to complete it depends on its size and design, the wages are generally calculated on the basis of the total number of knots a piece has. In the case of labour working at the traders workshops a worker is paid a stipulated amount per 1,000 knots. While most of the carpet weavers learn the craft in their homes at an early age, the community is receiving about three thousand entrants every year who are trained at more than a hundred carpet centres linked with an institution for teaching set up in Lahore in 1956.

Sindhi carpets are of two kinds, cotton durries and woollen farasis (derived from the Persian word farsh, floor). The flat-woven cotton durries are used as floor-coverings and are produced in a variety of colours and qualities. The earliest recorded durries had been made in jails in Khairpur, Hyderabad and Karachi.

A robust tradition of weaving carpets with wool, goat hair, camel hair, and mixed yarn exists in the tribal belts of Pakistan. The tribes in Balochistan weave ghilims with brightly coloured diamonds with woollen wefts on a woollen or goat hair warp. The variety of patterns and colours produced is large and varied. Similarly tapestries woven in the north-western tribal area and Chitral are called kalins. Mostly these bear bold geometric motifs in primary colours dominated by red. The kalins woven in Chitral are made of sheep wool on a cotton warp and the patterns are bigger than elsewhere. Chitral is also known for palesks, goat-hair rugs used as mats by the local people.

WOOL AND COTTON FARASIS

Woollen farasis and storage bags are woven by settlers of Baluch origin and the Mahars in villages in Kohistan, Guni, Kunion Ganwhar and Golarchi in Badin, around Ghotki in Sukkur and in Tharparkar. Patterns generally consist of coloured bands with fine, alternating geometric patterns. The quality and texture vary greatly according to the wool used for the weft. As dyed and undyed camel, goat and sheep’s wool are commonly used, the colours range from white, grey and black to shades of brown. Madder and indigo were traditionally used in the weft and consisted to a deep red and blue with green highlights. More recent combinations include the same colours using synthetic dyes with highlights in red, orange and silver thread being favoured. The warp continues to be made up of white cotton threads spun locally or purchased in neighbouring towns. The ends of the larger floor rugs, once the weaving is complete, are made into tiny plaits, with tassels added as a finishing tough.

Finely woven cotton farasis are used to sleep on and as prayer mats. A coarser version, woven entirely from camel or goat’s hair called khirir is found in villages in Kohistan and Badin and is used for saddle bags (khurzeen), nosebags (tobro) and for storing grain (boro). Women are usually responsible for weaving farasis and work in pairs on very simple ground-looms, using a floating weft technique. The looms are usually set up in shaded areas of the otaro or courtyard and covered when not in used, as women return to the task of weaving when they can make time from their household chores.