Chittaras are intricate wall paintings traditionally created by the tribal women of Malnad on their red mud-coated houses, as well as rangoli floor designs. Chittara paintings are part of a larger context of creativity and celebration in the cultural milieu of the region.

The chittara art-form however was almost extinct till it was revived recently by Eshwar Naik and his sister Lakshmi, Malnad tribals, who ‘re-discovered’ the artistic and cultural tradition of their forebears (their mother was a skilled chittara artist, with a rich repertoire of songs and music in which the art form was grounded. Eshwar Naik set up a training centre for chittara art, and is focusing on documentation work.

Wall paintings, by their nature, are transitory and celebratory. Every daily activity depicted in these paintings – grinding flour, pounding rice, sowing seeds – was enlivened with a song. The paintings depict the hustle bustle of tribal life – ceremonies, deities, socio-economic activities, flora and fauna, and even the toys the children play with. The art-form was also integrated symbiotically with the larger ‘natural’ context of this area in the Western Ghats, deriving substantially from nature natural cycles, and natural elements.

PRACTITIONERS & LOCATIONS

‘The Deewaru tribals’ huts spell magic with their age-old chittara Wall paintings ador[n]ing their walls…’. The villages of Hasunvanthe, Honemaradu, and Majina Kaanu (in Shimoga district of south Canara) are known for the chittara mural craft. Traditionally done by the women of Malnad, in south west Karnataka, for special occasions such as weddings, festivals and auspicious days, chittara wall paintings encapsulated an entire socio-cultural tradition, in which each motif and pattern symbolised an aspect of nature or depicted the religious, social or agricultural practices of the community.

COLOURS & MOTIFS

The community makes its own colours, deriving them from natural sources, such as barks of trees, rocks, minerals and vegetables. While the designs on the paintings are common across the entire community, the colours used distinguish one family or clan from another.

-

White is derived from a mixture of rice (threshed and pounded rice, made into a paste) and white mud

-

Red is made from crushed stone and the abundant red mud in the region

-

Black is also made from rice, which is burnt and then pounded

-

Yellow is made from the seeds of the gurige tree, special to Shimoga and Sagar districts in Karnataka.

According to National Award Winner Eshwar Naik, chittara painting ‘has an unbroken connection’ with ‘Stone Age cave paintings’. The motifs derive from everyday life and include geometrical shapes and tribal figures celebrating various aspects of life. The figures are usually stylised – representing brides and grooms, fertility symbols, the sowing of the auspicious paddy, birds, trees and animals. The designs are not particular to any one family, and are instead shared by the community. (However, different families have chosen ‘auspicious’ colours, though for the majority it is white.)

The painting is part of a much larger context of creativity and celebration. According to Pushpa Chari, ‘And lilting music fills the air as Deewarus draw and paint! For every situation and chore depicted on the wall, [there is] a relevant song, which too has been revived by Eshwar Naik.’

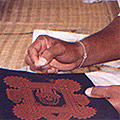

The delineation is done with fine jute pundi brushes, derived from the fibres of the pundi plant. Drawing is free hand.

CONTEMPORARY TRENDS

Chittara art has been given a broader forum in which the art-form is now found not only in Deewaru huts, but also on a range of artefacts that can access a much larger urban market. The community also makes decorative artefacts with the characteristic Chittara motifs on them. Chittara painting is being done on hand-made rice paper. The traditional paddy husk kalash can be found painted with chittara art, as can papier mache and terracotta vases. Cane baskets coated with red mud, bamboo pen stands, torans or door hangings made of dried paddy, hidi (small brooms made of hittade grass), sibala (baskets made of hittade grass), pettige (small box), irike (doughnut shaped ring of woven grass, ichala chaape (palm mat) are other items that can be found decorated with chittara motifs.

This adaptation has faced some opposition from elders in the community who strongly feel that the art-form and traditions should be kept within the community and not ‘displayed’ to the outside world.

Eshwar Naik is the craftsperson who almost ‘single-handedly’ resurrected chittara painting, as well as ‘ the entire culture of music, myth, belief and philosophy encapsulated in each line and motif’. Naik, when young, had moved away to dabble in street theatre and in literacy campaigns. The distance, he feels, helped him realise the need for documenting the rich legacy of his own community and cultural heritage before it was irrevocably gone. Naik’s sister Lakshmi was the sole surviving chittara artist at the time that Naik began to resurrect this art-form. Naik learnt the painting from his mother and sister, and collected motifs and myths from village elders. Owing to his efforts a large amount of the motifs have been recovered and documented. He even set up a training centre at Hasuvanthe – here young Deewarus rediscover their traditions and learnt the craft that their ancestors were proficient at.