Painting in Bhutan encompasses:

- Religious paintings: In the form of murals, thangkhas and manuscript illustrations. These are done by artists who follow a certain uniform style in creating what are not works of art but of faith – which they make as beautiful as possible, while scrupulously following the precise and symbolic iconometric and iconographic rules codified in ancient treatises. The act of commissioning and creating a religious painting is seen as a pious act that earns great merit and must be done with a pure mind.

- Decorations on furniture and window-frames: Nearly every house and building is colourfully painted with symbols such as a lotus, a dragon or the Tashi-Tagye as are furniture, tables and many objects that are a part of the daily lives of the people.

RELIGIOUS PAINTINGS

In Bhutan, religious paintings and ritualistic objects and buildings are not considered as just objects but as supports of faith that help in or enhance the understanding of the tenets of Buddhist philosophy and religion. Statues and paintings, books and stupas support the body, speech, and mind respectively of the Buddha.

Religious paintings are of three kinds:

- Murals

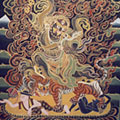

- Thangkhas

- Manuscript illustrations

Rules regarding proportion, thematic selection and consecration are fixed. They are the focal point of meditation.

TYPES OF RELIGIOUS PAINTINGS

- Murals in Dzongs and Monasteries

The dzongs, monasteries and temples contain incredibly beautiful works of art. Within their massive stone walls and measured wooden beams are found paintings representing important religious figures and mandalas, and narrative paintings portraying events in the life of a saint or other life stories. Many intricate and colourful illustrations serve as allegories, dramatising the continuing struggle between good and evil. - Thangkhas

Thangkhas are painted scrolls found in monasteries, using tantric symbols and natural phenomena such as water, fire and animal life. Since Bhutanese art is to serve primarily as a visual aid for understanding the tenets of Buddhist philosophy, a shrine could have one or more thangkhas. The themes of a thangkhas could be the Buddha; Guru Rimpoche; Tara; Wajra Kila-Phurpa; Sidpa Khorlo or the six realms of existence (God, demi-god, human life, animal life, hell and hungry ghost); Zambala, the God of health; Amitause, the God of Long life; Avlokisteshwara, or the God of Compassion. - Manuscripts – Calligraphy

In the past calligraphy has been practised as a fine art in Bhutan. Beautifully written manuscripts on separate sheets of centuries old handmade paper can still be seen in a surprisingly well-preserved state. Depending upon the nature of the text, the manuscripts also contain miniature paintings.The great importance given to books is reflected in the care that goes into writing and making them. Certain texts are written in calligraphy with ink made from gold dust and illuminated like medieval manuscripts in Europe. When the printing or calligraphy of a whole text is completed, the pages are bound between two wooden boards. The upper board may be a work of art in itself because it is often carved with religious subjects and perhaps covered with a sheet of wrought, gilded copper.

COMPOSITIONS/THEMES OF MURALS & THANGKHAS

These include depictions of:

- The Buddha in many forms

- Guru Rimpoche or the eight manifestations of Guru Padmasambhava – the great saint, who arrived in Bhutan in the year 800 AD.

- The 21 Taras

- Wajra Kila-Phurpa

- Sidpa Khorlo or the six realms of existence – God, demi-god, human life, animal life, hell and hungry ghost. The Wheel of Existence shows the six spheres of existence within which the sorrowful lives of non-enlightened beings take place. It is found hanging in temples as a meditational picture.

- The Wheel of Existence whose six different sections illustrate the world’s unreality to which every living being in this world is inextricably bound. The cycle of births and death, caused by human ignorance, is enacted here in all its sorrows and pains until finally it points to a path of salvation.

- Zambala, the God of health; Amitause, the God of Long life; and Avlokisteshwara, the God of Compassion

- The Tashi Tagye or the eight auspicious signs which are intimately associated with the life and teachings of the Buddha (refer article on Symbolism in Bhutanese Art).

- A mandala or khyilkhor – a sacred, cosmic diagram representing the universe. The mandala is basically a mystical pattern used for purposes of initiations and meditations. It was introduced in Bhutan together with all the teachings and methods of the Buddhist tradition, and its complex geometrical patterns are to be seen all over the country in a multiplicity of arrangements.

PRACTITIONERS CREATING MURALS & THANGKHAS

The requirements for the mandala masters and artists preparing sacred sculpture or paintings were the same: they had to purify themselves physically and spiritually first and meditate on the artwork they were to make. Over the years this has changed and the work of painting sacred scrolls of deities has been passed on to professional male artists.

Paintings and stupas are made by groups of artists working in workshops under the direction of a master. The apprentices do the basic work, while the master executes the detailed and fine work. Master painters in this manner pass on whatever special techniques they have to their apprentices or disciples. The methods by which this is done and the significance of each detail are passed down in an unbroken succession from master to disciple. The teachings involved are never divulged to those who have not been initiated. It is interesting to mention here that the chief masters of painting in the main state monasteries bear the designation of Khyilkhor Lobpon or ‘teacher of the mandala‘. This fact alone is sufficient to show the great importance given to this tradition in Bhutan.

THE MURALS OR WALL PAINTINGS

Madanjeet Singh in his book, Himalayan Art, says that the technique of applying colour on the walls and the manner of line drawing and composition in Bhutan are very similar to those in other parts of the Himalayas. They are essentially derived from the Ajanta methods (referring to the paintings in the Ajanta caves is western India), by which the pictorial composition is built around the central figure. The main – rather large – figure is the focal point toward which flock the adoring small divinities, while other diving beings, either singly or as part of scenes from stories, cover the outer area.

THE DEPICTION

The central figure is usually motionless – depicted in a static ritual pose. However, as the scenes spread out more and more some movement is felt, thus compensating to some extent the rigidity of the principal deity. The elements in the outer fringes are interlocked and are spread over the walls in line compositions that gradually unfold as the devotee walks along the wall from left to right.

Once a theme is picked up, different scenes can be made out in groups interconnected with subsidiary characters, animals or foliage. The events are not necessarily placed in sequence – often their interpretation becomes a very arduous task indeed, especially as the life stories of the different Siddhas greatly resemble each other. A factor of these rather stylised paintings is the use of bright colours and the interplay of broad areas of greens, depicting mountains, clouds and foliage as though reflecting the lovely Bhutanese landscape. They are undoubtedly inspired by the physical structure of the country – mountains, rivers, waterfalls, clouds, mists, cascades, hills and valleys – and from the abundance of flora and fauna as well as the natural phenomena of lightning and earthquakes.

COLOURS

The colour of the divine images, like its structure, is codified in rite and convention. In the older paintings there is uniformity in which a few colours – such as reds, blues and greens – predominate in soft shades. These pure colours are applied without any shading so that a figure does not emerge as a result of light and shade, but as a kind of pattern outlined to form shades.

|

|

|

|

METHOD

The method of painting employed in Bhutan is similar to the technique used for wall painting elsewhere in the Himalayas. On a moist wall, a series of coats of an emulsion of lime and gum were applied and then polished with a smooth surface such as a conch shell. An outline of the subject – beginning with the central figure – was then sketched in Indian ink or charcoal, according to the rules. Subsidiary figures were similarly drawn. Then the various colours in diluted form were applied with a brush in several coats. To strengthen the colour, the painting was covered with a varnish consisting of a mixture of glue lime and the appropriate colour. The colours used in Bhutan seem to be both organic and inorganic: cochineal for red, lapis lazuli for blue, arsenic for yellow and a mixture of arsenic with lapis lazuli in different proportions to produce greens in a variety of shades.

Gods are usually in the adamantine posture, holding the thunderbolt which signifies adamantine truth, or else in a meditative posture with hands in a gesture of blessing. It is the demonical deities – with protruding arms, swollen bellies, enormous teeth, weapons in their hands and ferocious expressions – who break all rules of iconometry.

THE GOINKHANG

A goinkhang is usually a small dark room in a lonely corner of the monastery, in the gloom of which are hung skins, nails, teeth of animals and also the remains of sacrificial victims or enemies together with their armour and weapons etc. In the goinkhang there is another group of wall paintings, which are reserved for the inmates of the demonic world.

THE SACRED

Artistic forms used directly for religious purposes include temples, dzongs, chortens and mani walls, thangkhas, wall paintings and images, and numerous ritual objects. Religious objects and buildings, stupas, paintings, statues, books and ritual instruments are sacred. A temple cannot be considered as completed without housing these three supports, which themselves become sacred. Painting, statues and stupas have life, symbolised by either a piece of wood covered with mantras or by mantras written at the back of the painting. A consecration ceremony that gives life to these objects is performed. The identification of these objects to the Buddha is so strong that it is a sin for people to rob or destroy them.

THANGKHAS

MATERIALS & TOOLS

- Canvas

- Wooden frame for the stretched canvas

(The sides of the canvas are folded and stretched with cords to make it stronger and properly stretched.) - Brushes of animal hair

- Paints: Made from carefully selected mineral sources – mineral pigments have to mixed with the size binder and the pigments themselves to produce another colour. (Size is actually a glue made out of skin of animals / leather boiled and dissolved. It is turned into gelatin. The size or binder is added to the pigments until it becomes a thick homogeneous liquid – the ideal consistency being like buttermilk. Traditional pigments are widely used but are more expensive than chemical paints. The colours used in Bhutan seem to be both organic and inorganic: cochineal for red, lapis lazuli for blue, arsenic for yellow and a mixture of arsenic with lapis lazuli in different proportions to produce greens in a variety of shades.

THE PREPARATION OF THE CANVAS

Thangkhas are normally painted on a cloth canvas. The canvas is put in lukewarm water with glue and lime and stretched on a wooden frame with a string.

The painting surface is now prepared. White colour with water is applied using a brush, cloth or a knife. The surface is then checked for tiny holes through which the paint can go through – if found, another coat of base paint is applied. Care has to be exercised in this process because if the coat is too thick then flaking and cracking could occur. The canvas also needs to remain pliant enough to be rolled up into a scroll and also unrolled.

The surface is then rubbed to make it smooth and polishing continues until the canvas has acquired the desired surface quality. The prepared canvas is known as dashu.

THE SKETCHING

The sketching of the main figure begins with the construction of the linear grid to conform to the physical dimension of the central deity. Angle of chest and head and the proportions of the body are fixed. The most important lines are the diagonals, which establish the vertical and horizontal axes. These lines determine the exact centre of the canvas around which the artist can plan the composition of the design. This actually marks the centre of the main figure, in relation to which all the other figures are positioned. A mistake in this respect can affect the accuracy and hence the religious value of the thangkha. The marking of the four borders follows with the artist leaving enough space of the edge for the brocade frame, which is stitched on when the thangkha painting is completed.

A single central figure is simple to delineate. The artist has only to draw the figure so that it fills most of the foreground. If the painting involves many figures there is a need to allocate greater or smaller spaces for the various figures, which depends again on their importance. Usually the artist determines the size of the main figure in the centre, and proceeds to allocate smaller areas in the form of ovals or circles for minor figures.

Thangkha painters are usually familiar with Buddhist iconometry traditional artistic practice, and hence they are regarded as being acquainted with proportions, configurations and characteristics of deities. There are various ways in which a sketch is made on the canvas – the design could be sketched/ traced/ xylographed. The master artist could create the tskpar or sketch using a pencil; alternatively, if the composition is well known, xylograph blocks are carved and used to print on the canvas. Often, if the sketch is simple – such as the single figure of the Buddha or Tara – it is first drawn on paper for use as a stencil. The sketch drawn on the stencil is punched with needles thus creating small holes on the paper. The stencil is placed on the canvas and red powder is then dusted on to it thus creating an outline on the canvas.

When the initial sketch has been completed the master checks the proportions of each figure by comparing certain key measures of height and breadth of each figure. Satisfied with his figures he surrounds them with sketches of pleasant landscape and ornaments, clouds, mountains, greenery, lakes and waterfalls. And lastly he adds details, such as flowers, jewels and auspicious animals as offerings. The canvas is now ready for introducing the colours.

THE PAINTING

Painting involves filling in the areas with different base colours and subsequent shading and outlining of these areas.

Mud or mineral colours are used. However, since some of these are dull, chemical colours are also used. These paints are in the main prepared by the artists themselves – on the whole by mixing pigments with the sizes binder, and by mixing the pigments themselves to produce another colour.

Colours used in a thangkha painting can be classified into three categories:

- Mild for the bodhisatvas;

- Slightly stronger for tutelary images and other creatures; and

- Bold dark colours like black and blue for the terrifying deities.

On completion of the painting the canvas undergoes dry polishing on its back to make it soft or pliant and resistant to cracking. A fine quality thangkha can take as long as four or five months to complete.

THE ICONOMETRIC RULES

Madanjeet Singh, in his book Himalayan Art, writes that, the art of Bhutan synthesises many strains – Indian, Nepalese, Chinese and Central Asian. Stylistically, perhaps one of the most dominant influences is the Nepalese.

The canons of art became more or less permanently established – they were replicated generation after generation. This was not because the artists could do no better but because it was believed they merit accrued to them through replicating. In the grotesque world of fantasy (demons) the artists apparently had a greater freedom of action than when modelling images of gods. As in the drawing of divine figures, Indian iconometry set the rules for bhayankara or terrifying figures. The artist however had apparently greater freedom of action here as long as he successfully enlarged and improved upon this grotesque world of frenzied terror. Examples of these paintings can be seen in the Goinkhangs.

Buddhist art is concerned with highlighting certain important values associated with spiritual experience. The role of the artist is therefore to transmit such teaching through their art. The iconographical conventions are thus very strict, and artistic freedom may only be expressed in minor background details.

The National Museum at Paro explains that the iconometric rules are not established at random – proportions are laid down in the records. A painter must know the exact unit of measurements of each deity to develop into a sketch. Six major proportional classes known as Thig Chen – great lines – are as follows:

- Buddha

- Peaceful boddhisatvas

- Goddesses

- Tall wrathful figures

- Short wrathful figures

- Humans

Each of the above has sub-unit measurements for each deity depending on their posture. Each gesture signifies an abstract principle. The rules of iconography and iconometry are strict and firmly established and must be scrupulously respected. Each deity has a colour and special attributes that cannot be changed without altering the meaning of the religious function. The artist therefore cannot express himself except in small details or painting of minor scenes.

Each God is assigned special shapes, special colours and special attributes (to hold a lotus, a conch-shell, a thunderbolt, a begging bowl). All holy images have to be made to exact specifications – these precepts have remained remarkably unchanged for centuries. The dimensions of religious works have been precisely detailed in the scriptures and before any colour can be added to a work many hours must first be spent drawing the figure or design exactly as it has been for centuries.

MOUNTING ON BROCADE

Once complete, thangkha paintings are mounted on brocade – only a few tailors are specialised enough to know how to stitch thangkhas. The colour of the brocade will depend on the colour of the thangkhas. Every thangkhas will have a sherimasi – these are the yellow and red borders around the thangkhas. A thangkha will also have a shekhep – a piece of cloth to cover the thangkhas. The shekhep is traditionally in two colours – yellow and red.

CONSECRATION

Lay believers generally commissioned thangkha paintings. Commissioning and possessing thangkha was mainly inspired by the belief that it accrued enormous merit to the painter as well as the person commissioning it and ensured a life free of difficulties, diseases, or obstacles. The commissioning of a thangkha was often recommended to remove physical or mental obstacles or for a long and healthy prosperous life.

Once complete, thangkha paintings are consecrated in a special ceremony, whereby they come to personify the deities they depict. The Lama consecrates the painting by writing at the back and putting his seal. Consecrated thangkha have a date of completion and consecration, personal mantra of owner and reason why they were commissioned, among other details, followed by some prayers usually for wealth or long life.

PRODUCTS

Thangkha are valued not merely as religious artefacts but also as artworks. As sacred paintings they were not supposed to be sold, but there is now a great demand for them. They need no longer be commissioned – they are now available in the market.

PRESENT STATUS

The Bhutanese Government is promoting the training of new artists, under the guidance of masters. On completion of their training, these artists are employed by the government in painting murals and thangkhas and in decorating official buildings through out the country. These artists are also using indigenous Bhutanese mineral and vegetable paints, which are so well suited to the style and purpose of Bhutanese art and to the climate.

The National Technical Training Authority has instituted the Quality Seal – With the aim of promoting thangkha painting in Bhutan. The quality seal can be found on the back of the thangkha.

In the Kingdom of Bhutan, arts and crafts play an ever increasingly vital role in the country, socially, politically and economically. It is for this reason that the Thangkha Development Committee was formed at the beginning of 2000. The present Chairman of this committee is Lyonpo Sangay Ngedup. Members include many renowned senior artists. The purpose of this committee is to improve the quality of traditional Bhutanese thangkhas.

Due to modernisation and tourism there is a constant threat of degradation of quality standards, which are of utmost importance in traditional Buddhist art. One can find sad examples of this phenomenon in neighbouring countries where mass produced thangkhas have flooded the market, exemplifying the tendency of some artists to make a quick buck from their work.

The aim of the Thangkha Development Committee is to remind both the producers as well as the buyers of thangkhas that the standards of Buddhist art, as specified in the sacred texts, must be met with. With this in mind, The Thangkha Development Committee is attempting to combat:

- Usage of pigments of bad quality.

- Lack of details in the background and on robes of deities.

- Disregard for proportion in the basic drawing.

- Inappropriate colours, tones and subject matter.

- The over use of shading in faces of deities.

- Improper stitching of the brocade frame.

This Committee judges and gives quality seals to all thangkhas in the kingdom which meet the specific quality requirements. Once a quality seal has been obtained, artists are able to sell their work for a higher price, and the buyers will know that thangkha with the quality seal will be of good value. In the years to come the committee will provide quality seals to all areas of the ‘Zorig Chusum’, the 13 aspects of traditional arts and crafts. Marketing will be done through exhibitions and competitions annually. This will encourage the artists to work to their best ability and Bhutanese thangkhas, sculptures, embroidery and other arts, will be synonymous with quality throughout the world. These products will be marketed through local galleries, the Zorig Chusum Institute, the internet and exchange program with renowned museums abroad.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN A COMMERCIAL THANGKHA & QUALITY THANGKHA

-

Style of Painting: The main difference between a quality thangkha and a commercial one is in terms of proportion. In a quality thangkha the dimensions are perfect and correspond accurately to instructions given in the sutras (Buddhist texts)

Quality paintings in most cases are shaded in ‘Kamdang’ style (dry shading), while commercial thangkhas are shaded in ‘Lemdang’ style (wet shading). ‘Kamdang’ can be clearly identified as small horizontal strokes of paint in the sky and on the hills, and as small soft dots of colour on clouds and flowers. It is a long procedure where a square inch of area could take perhaps a day to be filled. Lemdang can be identified as a smooth gradation of colour and is quickly accomplished.

The outline of the eyes, face, fingers, and feet in quality thangkhas are detailed, accurate and perfect. The commercial paintings will not have such details. The halo of the deities for quality thangkha painting will have a perfect circle whereas some irregularities can often be found in commercial paintings.

The gold decoration on the painted surface of a quality thangkha will shine when tilted against light whereas the artificial gold on a commercial thangkha will not.

- Duration: An average quality painting could take many months or even years of continuous daily labour, whereas the same subject matter in a commercial thangkha could be completed in 2 to 14 days.

- Brocades Frames: On a quality thangkha the back of the canvas will be exposed and a mantra written on it. The plain cloth covering on the sides of the back part of the brocade will be stitched manually on to the edges of the thangkha itself. The outer silk cover will have another colour of silk at the sides that are slightly overlapped. There will be a pair of carved rings hooked against the top bar to hold it upright. The top ends need to be stitched with leather protection squares on the back. The ‘toke‘ or the knobs at the bottom ends will be carved silver with gold gilding. The silk cloth will be of the highest quality possible and sewn with accurate straight stitches following the rules of proportion. The corners of the brocades must have a perfect angle and the painting must hang straight.A commercial thangkha painting will probably be covered by a single yellow piece of cloth. The backside of the painting could be covered entirely by plain cotton without mantras. The painting could be decorated with artificial gold designs. The top will probably be plain with no hooks or rings. The knobs could be of cheap metal only and most probably the stitching will be not straight.

- Rates: A commercial thangkha painting may cost Nu. 1,500 upwards. A quality thangkha can cost a minimum of Nu. 15,000.